Since the very early versions of TypeScript, the language provided support for the class keyword, together with some additional features, that you find in classic object-oriented languages.

In this article we will discover how TypeScript helps us create classes and how it transforms JavaScript into a more traditional OOP experience. I will explain how to add types and how to implement inheritance, enforce private and protected members, add accessors and abstract classes. We will then talk about the structural type system of TypeScript, which differs from the other flavors of OOP, you may probably be familiar with.

But first, let’s revisit what we’ve learned about classes and how JavaScript defers from it. This will help you have a better understanding of what’s going on.

Sandae? 🍧

Let’s talk about objects, first

There are multiple ways to create an object in JavaScript. Here’s the most convenient and common way:

const track = {

title: 'Bohemian Rhapsody',

artist: 'Queen',

releasedAt: 1975,

}Now, in contrary to other languages, nobody stops me from editing this object by adding or changing its properties:

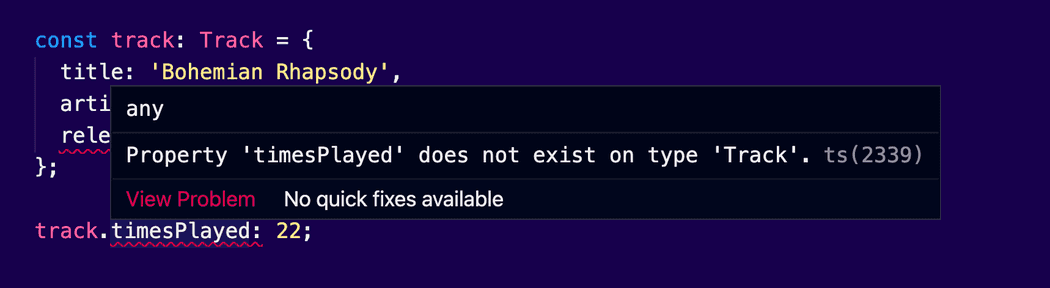

track.timesPlayed: 22;Nobody except TypeScript of course. Here’s the same example, after adding types:

type Track = {

title: string;

artist: string;

releasedAt: string;

}

const track: Track = {

title: 'Bohemian Rhapsody',

artist: 'Queen',

releasedAt: 1975 // Type error: not a string

};

track.timesPlayed: 22; // Property 'timesPlayed' does not exist on type 'Track'And here’s the error I will get when I try to set a value to a property that doesn’t exist:

Brilliant! Now we can relax because our objects will follow a structure. There are rules in the game. TypeScript acts again as a guard against typos or common mistakes.

Although, this adds a lot, we still have the problem of how to organize our code. You see, types are perfect for protecting us from errors, but they simply don’t exist at runtime. TypeScript will remove those types altogether, when it will compile our code to JavaScript.

We need a better tool to define object structures and their relationships.

Photo Credit: Debby Hudson

Photo Credit: Debby Hudson

What is a class?

A class is a blueprint for an object.

Think of it as a higher-level data type, similar to how you use const or let.

const xSimilarly, you can use a class to create objects that have a specific structure:

MyClass myObject;In this example we have a class MyClass and we instantiate the object myObject. Note that classes, by convention, start with a capital letter (PascalCase) but objects, like any other variable by convention, start with a small letter (camelCase).

Matt Weisfeld, in his book “The Object-Oriented Thought Process”, resembles a class as a cookie cutter. You take the cookie dough and you use the cookie cutter to make the cookies. That’s how you can use a class to instantiate objects.

Classes help us organize our code. Instead of having your code in a bunch of functions and variables, that are unrelated to each other, you can structure everything into a class.

In most programming languages, a class is used to create an object. It describes the contents of objects that belong to it. The data fields that it contains, and its operations. We call those properties and methods accordingly.

The ugly truth

As you may already know, there are no classes in JavaScript.

It is a prototype-based object oriented language. This basically means that any object in JavaScript inherits properties and methods from a prototype. This prototype could be another object, or one of the built-in objects.

This maximizes code reuse. Think of it like a traditional class inheritance, but without the necessity of defining everything upfront.

It’s easy to follow a prototype chain. Just try to get the prototype of a date variable:

const date = new Date()

Object.getPrototypeOf(date) // returns a reference to DateUp until now, in JavaScript, you couldn’t define the relationships of the objects upfront using a class. You had to create objects that inherit from other objects. There was a need to have a more sophisticated way to create objects with a given structure. That’s why JavaScript developers were used to leverage plain functions to create objects. They worked exactly as constructors.

Take a moment to review the functional constructor below:

var Track = (function () {

function Track(title, artist, releasedAt) {

// set default values

this.title = 'Untitled'

this.artist = 'Unknown Artist'

this.releasedAt = 'Unknown Release Date'

// assign values passed via arguments

this.title = title

this.artist = artist

this.releasedAt = releasedAt

}

return Track

})()It’s quite an inconvenient way to write code, don’t you think?

Since ES6, we can simply use the class keyword to define classes:

class Track {

title = 'Untitled'

artist = 'Unknown Artist'

releasedAt = 'Unknown Release Date'

constructor(title, artist, releasedAt) {

this.title = title

this.artist = artist

this.releasedAt = releasedAt

}

}This is just a syntactic sugar. In the background it still works exactly as before.

TypeScript to the rescue

TypeScript was one of the first languages that provided support for creating classes. Any valid JS class declaration is valid in TypeScript as well.

Depending on the compiler configuration, you have to define types for the class members.

Remember the previous example? Let’s add some types on it:

class Track {

title: string = 'Untitled' artist: string = 'Unknown Artist' releasedAt: string = 'Unknown Release Date'

constructor(title: string, artist: string, releasedAt: string) { this.title = title

this.artist = artist

this.releasedAt = releasedAt

}

}Here’s how we can create an object from our class, by consuming its constructor:

const track = new Track('Bohemian Rhapsody', 'Queen', 1975)As you may have noticed, we don’t explicitly specify a type for the track object. TypeScript will automatically set that this is an instance of Track. There is a way to explicitly define the type, though:

const track: Track = new Track('Bohemian Rhapsody', 'Queen', 1975)Many developers prefer this way, because it’s much more readable. If you use a function that returns an object, for example, you will miss the information in your head what kind of object our track was. It’s a detail, I know. But it helps a lot!

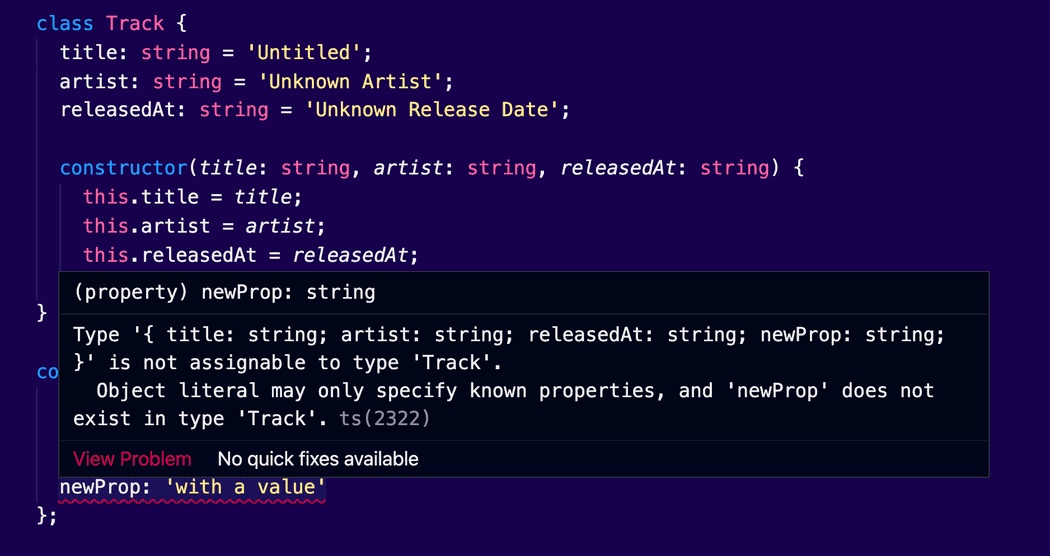

Now, let’s try to add a new property that doesn’t exist in the class definition:

const track: Track = {

title: 'Bohemian Rhapsody',

artist: 'Queen',

releasedAt: '1975',

newProp: 'with a value',}Yes, my friends, you guessed it correctly. We will get an error:

In JavaScript, when a variable doesn’t have a value, it’s undefined. The same applies for our class properties. We could leverage the usage of unions to allow undefined values:

class Track {

id: string | undefined title: string = ''

artist: string = ''

releasedAt: string = ''

constructor(id: string, title: string, artist: string, releasedAt: string) { this.id = id this.title = title

this.artist = artist

this.releasedAt = releasedAt

}

}We could also have optional properties with the ? character:

class Track {

id: string | undefined

title: string = ''

artist: string = ''

releasedAt: string = ''

isFavorite?: boolean

constructor(

id: string,

title: string,

artist: string,

releasedAt: string,

isFavorite?: string

) {

this.id = id

this.title = title

this.artist = artist

this.releasedAt = releasedAt

this.isFavorite = isFavorite

}

}Here, the isFavorite flag can be completely omitted when we are instantiating object from this class. Basically, this means its value will be undefined.

Photo Credit: Eugenia Kozyr

Photo Credit: Eugenia Kozyr

Structural type system

This is one of the most difficult concepts of TypeScript, for people who are not familiar with JavaScript. It’s the way the language checks the compatibility of the types.

Here’s a simplified version of what is possible in TypeScript:

const track: Track = {

title: 'Bohemian Rhapsody',

artist: 'Queen',

releasedAt: '1975',

}Here, we’re basically bypassing the constructor altogether. We are creating an object, using an object literal, and then we’re passing this object to a track variable. TypeScript will compare the shape of this object with the shape of the class Track. If there are no type violations in its methods, no errors will be thrown.

Now let’s see a different example:

class Dog {

name: string = 'Nobody'

}

class Cat {

name: string = 'Nobody'

}

const cat = new Cat()

const dog = new Dog()

const animal: Dog = catHere these two objects originate from completely different classes. We have a Cat and a Dog. But observe what is happening if I assign a cat to a dog. No errors whatsoever.

Somebody will argue how good this approach really is. TypeScript has to be more flexible here, because JavaScript doesn’t have types. And strategically speaking, backwards compatibility is really crucial. That’s why they had to use a concept called duck typing. Duck typing in computer programming is an application of the duck test:

“If it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck”

In the example above, both these objects have a name property, which is of course public. That makes them practically compatible.

Inheritance

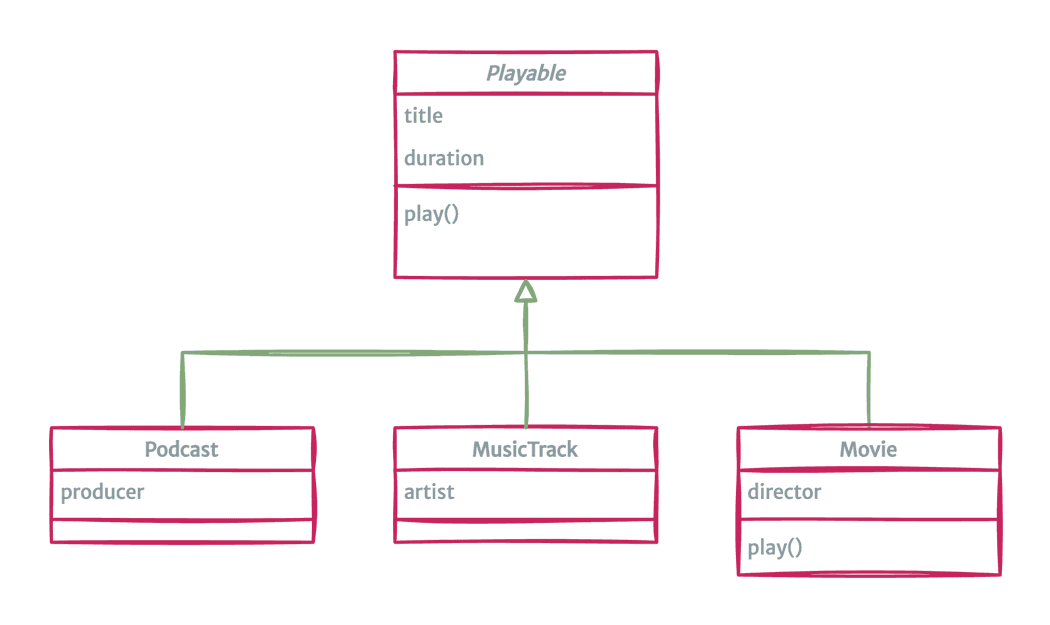

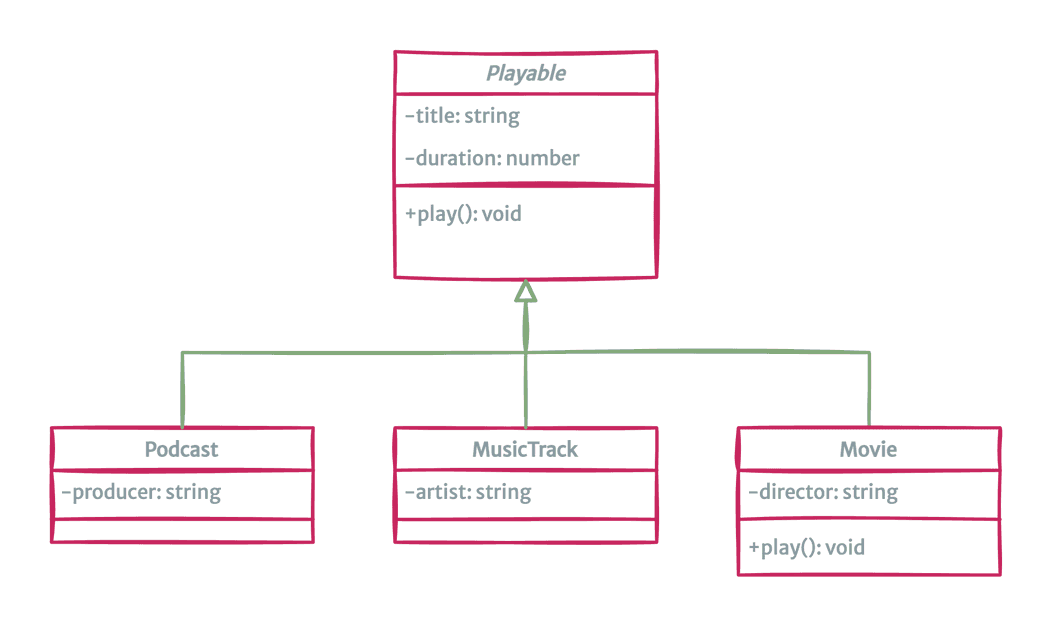

In the following example, I’m declaring a Playable class, and I’m using it to create three additional classes that derive from it:

Here is how we can implement it in TypeScript:

class Playable {

title: string

duration: number

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number) {

this.title = newTitle

this.duration = newDuration

}

play() {

console.log(`Playing "${this.title}"...`)

}

}

class MusicTrack extends Playable {

artist: string

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number, newArtist: string) {

super(newTitle, newDuration)

this.artist = newArtist

}

}

class Podcast extends Playable {

producer: string

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number, newProducer: string) {

super(newTitle, newDuration)

this.producer = newProducer

}

}

class Movie extends Playable {

director: string

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number, newDirector: string) {

super(newTitle, newDuration)

this.director = newDirector

}

}Note that I’m using the extends keyword, which is another feature of JavaScript.

I can then instantiate an Movie object:

const myMovie = new Movie('The Godfather', 175, 'Francis Ford Coppola')

myMovie.play() // Playing "The Godfather"...Now, let’s try to override the play() method of the class Movie:

class Movie extends Playable {

director: string

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number, newDirector: string) {

// calls the constructor of the parent class

super(newTitle, newDuration)

this.director = newDirector

}

play() { console.log(`Playing "${this.title}" by "${this.director}"...`) }}And, as expected, when we call the play() method, the message that we get is different:

const myMovie = new Movie('The Godfather', 175, 'Francis Ford Coppola')

myMovie.play() // Playing "The Godfather" by "Francis Ford Coppola"...Private & protected methods

Class properties and methods are kinda useless without specifying their privacy. In the previous example, I can directly change the values of the properties or call the play() method, from anywhere in my code:

myMovie.title = 'broken title'

myMovie.play() // Playing "broken title" by "Francis Ford Coppola"...In a real-world application, you wouldn’t allow anyone to access our class members directly. In fact, this privacy is one of the key benefits of OOP.

An improved version of our previous design can be the following. Our ultimate goal is to protect the properties:

TypeScript adds better support for private methods. It’s important to remember that the following keywords are only available during compilation, and they aren’t available at runtime. Nothing protects you from accessing their values. If you really need that protection, ECMAScript 2015 has support for private properties or methods. But I would say it’s syntax is quite weird. So use it only in rare cases, when it’s really important to protect your objects.

By default, all class members are public. You can omit the public keyword. Here’s what we’ve meant in the previous example, when we were declaring the class Playable:

class Playable {

public title: string

public duration: number

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number) {

this.title = newTitle

this.duration = newDuration

}

public play() {

console.log(`Playing "${this.title}"...`)

}

}To restrict access to our properties, we can use the private keyword:

class Playable {

private title: string private duration: number

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number) {

this.title = newTitle

this.duration = newDuration

}

play() {

console.log(`Playing "${this.title}"...`)

}

}An attempt to change the title will fail:

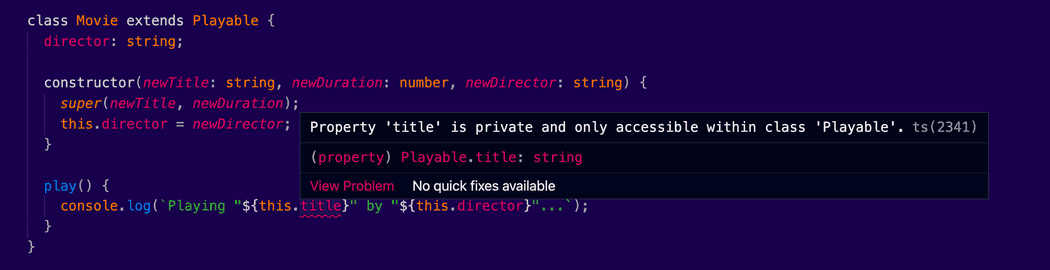

myMovie.title = 'broken title' // Error: Property title is private and only accessible within class PlayableThat’s very convenient and secure. As a side effect, we can’t even access or change this property from within the derived classes. You will notice that now our Movie class, has a very interesting error:

We can use the protected keyword, to allow accessing class properties, or methods, from derived classes:

class Playable {

protected title: string;

protected duration: number;

...

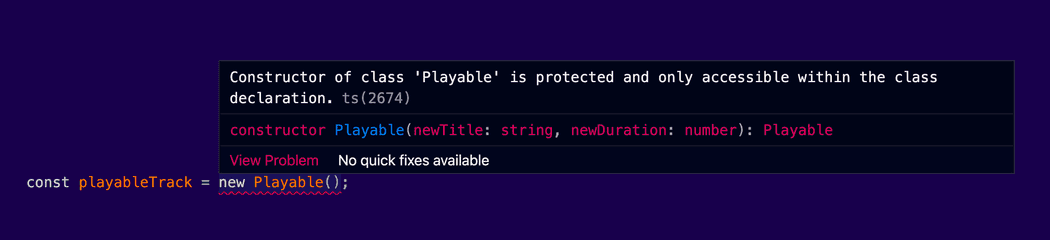

}A constructor can also be marked as protected. This means that the class cannot be instantiated outside its containing class, but can be extended.

For example, if we set our costructor to protected:

class Playable {

protected title: string; protected duration: number;

protected constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number) { this.title = newTitle;

this.duration = newDuration;

}

...

}

const playableTrack = new Playable(); // throws an errorWhich doesn’t allow my to access:

It won’t be possible to instantiate new objects from the Playable class:

We can use the readonly keyword to define properties that behave as constants:

class Playable {

protected readonly title: string; protected readonly duration: number; ...

}Properties that are marked as readonly, cannot change, even within derived classes:

class Movie extends Playable {

director: string;

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number, newDirector: string) {

super(newTitle, newDuration);

this.director = newDirector;

this.title = ''; // cannot assign to title because it is a read-only property }

...

}Accessors

We can use setters and getters in combination with our private properties:

class Playable {

private _title: string

private _duration: number

get duration(): number { return this._duration } set duration(newDuration: number) { if (newDuration && newDuration < 0) { throw new Error('Duration cannot be negative') } this._duration = newDuration }

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number) {

this._title = newTitle

this._duration = newDuration

}

play() {

console.log(`Playing "${this._title}"...`)

}

}Here, I’m using an underscore _ as a prefix to differentiate the private properties. It’s a common naming convention.

These accessor functions can have their own logic. For example, we check for negative duration values.

Here’s how we use them:

const playableTrack = new Playable('something', 111)

playableTrack.duration = -1 // throws an error, Duration cannot be negativeAccessors with a get and no set are automatically inferred to be readonly.

Guarding methods with types

Now let’s try to write our custom method:

class Playable {

private _title: string

private _duration: number

get duration(): number {

return this._duration

}

set duration(newDuration: number) {

if (newDuration && newDuration < 0) {

throw new Error('Duration cannot be negative')

}

this._duration = newDuration

}

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number) {

this._title = newTitle

this._duration = newDuration

}

play() {

console.log(`Playing "${this._title}"...`)

}

getDurationTime(): string { const hours: number = Math.floor(this._duration / 60) const minutes: number = this._duration % 60 return `${hours}:${minutes}` }}Everything that applies to functions can be used for defining methods in classes.

const playableTrack = new Playable('something', 111)

console.log(playableTrack.getDurationTime()) // 1:51I don’t know if you agree with me, but this hardcoded 60 value looks kinda odd to me. We can refactor it using the static keyword:

class Playable {

static minutesPerHour: number = 60; private _title: string;

private _duration: number;

...

getDurationTime(): string {

const hours: number = Math.floor(this._duration / Playable.minutesPerHour); const minutes: number = this._duration % Playable.minutesPerHour;

return `${hours}:${minutes}`;

}

}Ah much better! I feel like I’m writing C# now.

Abstract classes

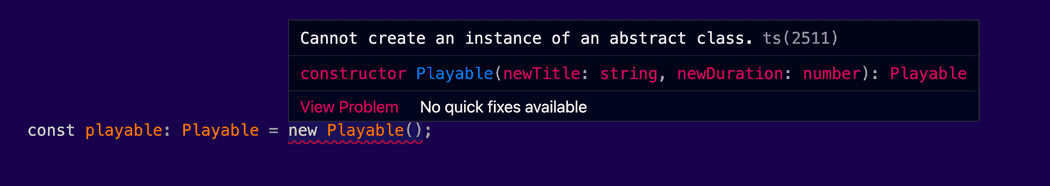

TypeScript adds support for abstract classes:

abstract class Playable {

protected _title: string

protected _duration: number

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number) {

this._title = newTitle

this._duration = newDuration

}

abstract play(): void // must be implemented in derived classes

}For starters, we cannot instantiate objects from an abstract class:

Abstract classes allow us to define abstract methods. These are methods that don’t have any implementation, but we expect from the derived classes to implement them. We only define the signatures of those abstract methods. TypeScript will make sure they are followed by the book.

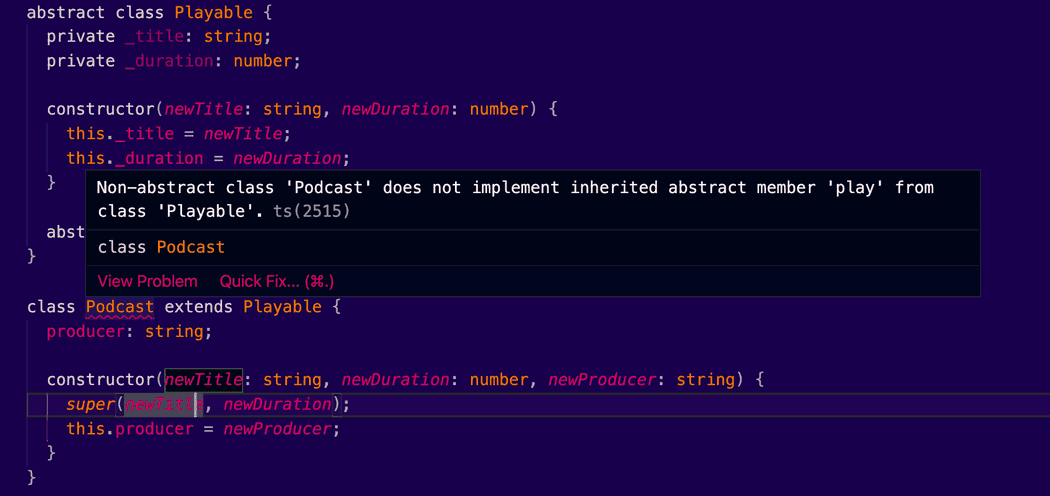

To illustrate this in practice, consider the following derived class:

class Podcast extends Playable {

producer: string

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number, newProducer: string) {

super(newTitle, newDuration)

this.producer = newProducer

}

}In the previous example, we extend the class Playable, to create a Podcast class. Note that if we fail to implement all its methods, we will get a very informative compilation error:

Now let’s fix this, by implementing the play() method:

class Podcast extends Playable {

producer: string

constructor(newTitle: string, newDuration: number, newProducer: string) {

super(newTitle, newDuration)

this.producer = newProducer

}

play() {

console.log(`Playing "${this._title}"...`)

}

}We can use our Podcast class to create podcasts:

const myPodcast: Podcast = new Podcast( 'A podcast title',

90,

'Nicos Tsourektsidis'

)

playable.play()

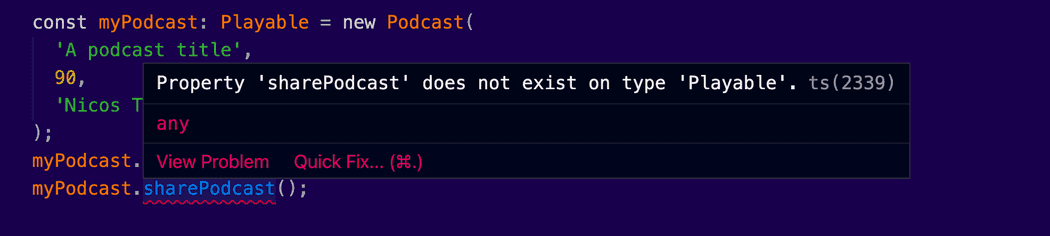

playable.sharePodcast()And here’s where the magic begins. We can use the type of the abstract class Playable to indicate that our variable can host any object from classes that derive from Playable:

const playable: Playable = new Podcast( 'A podcast title',

90,

'Nicos Tsourektsidis'

)

playable.play() // This is defined in the abstract class, it will work

playable.sharePodcast() // This method will not work, it's not definedAnd now we have access to all the methods and properties that exist in the Playable class. This allows us to perform high-level actions on a variety of objects that have completely different implementations.

If we try to access a method or a property that’s not defined in the parent abstract class, this will thow an error:

Cover Credit: Nataliya Smirnova