Interfaces help us define the shape of our object structures.

An interface can act as a blueprint for a class, allowing us to add common functionality to unrelated objects. We use this feature to organize our code, by making it easier to follow and scale.

In TypeScript, interfaces can be used as type annotations, similar to class, type aliases, and other built-in types. This helps us guard our code against types. This strict type system protects us from common errors, which eventually speeds up our development times.

It also helps our code editor to have a better understanding of how our code is interconnected, and provides much more sophisticated auto-completion suggestions.

In the following paragraphs I’m going to explain in detail what an interface is and how you can use them in your code. I will give you some practical use cases, which will help you recognize where you have to use interfaces in your code. Before I leave you, I will explain the concept of declaration merging, which is one unique characteristic of interfaces.

🍦Soft Ice cream?

Why the hell I need another keyword?

Consider the following track object:

const track = {

title: 'Bohemian Rhapsody',

artist: 'Queen',

isFavorite: true,

}In a traditional JavaScript project, that’s a very convenient way to define objects. This specific one contains everything we need to know about a music track. Such object structures are created on the fly, as we interact with the different modules and packages of our application.

Objects can store anything. An api response. An event payload. Some configuration parameters. Information about styling, animations and many more. The simplest way to deal with such object structures is to create classes with all your models. But what about objects you can’t control, such us browser event payloads?

In the beginning, it didn’t cost anything to come up with object structures like these, so we went for it. As we go along we are adding more and more object structures. As the codebase grows, some of these object structures may already be defined somewhere else in our project. And you know what they say, duplication should be avoided.

Most of the times, it is difficult to recognize such duplications. You see, I may want to name the title of the track title, but maybe you had another naming convention in mind. Maybe you disagree with the schema of the response, or maybe you want to use underscores, for reasons unknown. And then another person joins the team and suddenly we have three different names. Now we have to collaborate with another team, which has three more different naming schemes for the same concept.

We need a way to be able to quickly form data shapes, without implementing anything about them. That’s an interface. It describes the shape of these objects.

What is an interface?

Historically, this was the main reason to use an interface. Classical object oriented programming languages, such us Java, and C#, also have interfaces that work similarly. This concept is similar to the protocols of Objective-C and Swift. But JavaScript is a dynamic language. The concept of interfaces has evolved to be another way of guarding variables with type annotations.

An interface describes the shape of an object structure.

An interface is like a set of instructions that describe the data and the behavior of an object. You can’t implement its methods; you can only describe their signature.

We can use interfaces as any other type annotation, to help TypeScript understand what is expected for a specific object variable. TypeScript will enforce a strict policy on that variable, to make sure that the instructions you set upfront are met. It will check the names of its properties, their types, and their restrictions. It will also check the names of the method functions, along with all their associated parameters and their return values.

An interface can also be used to define the shape of a class. In the previous article we saw that a class is a blueprint for an object. In a similar way, an interface acts as a blueprint for classes. Classes implement interfaces, which means they strictly adhere to the shape of them.

Creating & consuming interfaces

Let’s define an interface about a music track:

interface IsTrack {

// required properties

id: number | undefined

title: string

artist: string

// optional properties

releasedAt?: number

genres?: string[]

}The interface Track, defines the expected shape of these objects. That includes properties and their associated types. The properties releasedAt and genres are optional. No big surprises here compared to what we know about other types, right?

Now, imagine the following JSON structure, as an api response:

[

{

"id": 1,

"title": "Bohemian Rhapsody",

"artist": "Queen",

"isFavorite": true

},

{

"id": 2,

"title": "Dream On",

"artist": "Aerosmith",

"isFavorite": true

}

]We can store this response using our newly defined interface:

const tracks: IsTrack[] = apiResponseAs you can see, we used an interface similar to how we would have used a type.

Interfaces can also contain function signatures:

interface IsTrack {

id: number | undefined

title: string

artist: string

releasedAt?: number

genres?: string[]

setFavorite(id: number, isFavorite: boolean): void}By adding a setFavorite() method to our IsTrack interface, the previous response becomes incompatible. The consumers of this interface must implement these additional two functions to modify favorites.

As we’ve seen, interfaces become useful when multiple teams are working on the same project. A team may decide to name their properties differently. By creating interfaces and by storing them in a central place, you are avoiding this mess. You all know what a Track is and what it needs to deal with it. The other team can now develop their part, without having any working code from your side. They just depend on the interface you have provided.

You can export interfaces to make them available outside your project:

// track.ts

export interface Track { id: number | undefined;

title: string;

...

}This can become very useful when you are creating a shared library. Now, we can import this interface and use it:

// another.ts

import Track from './track';

function TrackList(tracks: Track[]) {

...

}Yeah, I know. I have an issue with the music tracks in this series. I am going through a phase. It will pass. I just need some time with myself.

Where can I use interfaces?

If you are wondering where and when to use interfaces in your projects, you are not the only one. This has bugged many JavaScript developers, including the author. You see, we never had to deal with classical OOP concepts.

TypeScript has added a lot of flexibility to its interfaces, to support the JavaScript language. In this section, we will review the most important use cases of using interfaces.

Using Interfaces to implement unrelated classes

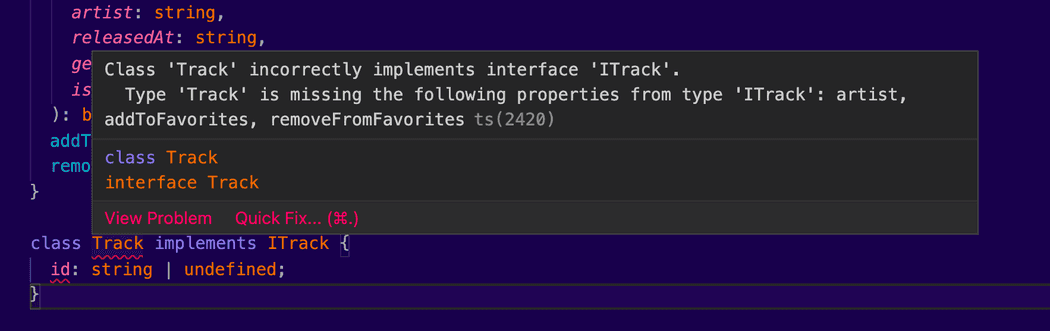

So far, we have been using interfaces as types. But interfaces work great with classes. Mind the new keyword implements:

class Track implements IsPlayable {

duration: number

play(): void {}

}I know what you are thinking. This class doesn’t implement our interface fully, and TypeScript will let us know about that. But that’s why we have the interface, right?

We can combine multiple interfaces to mix and match the functionality we want to inherit.

Consider the following interfaces:

interface IsTrack {

id: number | undefined

title: string

artist: string

// Optional properties

releasedAt?: number

genres?: string[]

}

interface IsPlayable {

duration: number

play(): void

}

interface IsFavorable {

isFavorite: boolean

toggleFavorite(): boolean

}The IsTrack interface describes the shape of a track object. It’s similar to a model in MVC. The interface IsPlayable marks an object as playable, which means we expect these objects to have a duration and a play() method that we can call. Similarly, the interface IsFavorable describes classes that provide this functionality to get the favorite boolean and toggle its value using the toggeFavorite() method.

Now let’s put these interfaces together to create our Track class:

class Track implements IsTrack, IsFavorable, IsPlayable {

id: number | undefined

title: string

artist: string

isFavorite: boolean

duration: number

constructor(

id: number,

title: string,

artist: string,

isFavorite: boolean,

duration: number

) {

this.id = id

this.title = title

this.artist = artist

this.isFavorite = isFavorite

this.duration = duration

}

toggleFavorite(): boolean {

const newValue = !this.isFavorite

this.isFavorite = newValue

return newValue

}

play() {

console.log('playing...')

}

}In this example, we are combining both three interfaces. Try this example by yourself and notice the TypeScript errors as you add more functionality to your class. Also, notice how your editor provides better auto-completion, as you define the expected class members.

Using interfaces to define the shape of object structures

The nature of JS is open. Data comes from multiple sources. Maybe you are consuming the YouTube api and you want to deal with its response. Maybe the user clicks on a button, or types something in an input. Maybe you want to call a helper function and pass a collection of these entities.

You can create an interface next to your code to annotate this specific part of this interaction.

Consider the following example, where we want to fetch some music tracks using the fetch api:

let mixtape: IsTrack[] = []

fetch('http://example.com/tracks.json')

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((data) => (mixtape = data))Here, we use the IsTrack interface we declared above, to annotate the type of the mixtape. We know this object pretty well, because it’s a part of our application’s business logic.

You also have the option to declare these interfaces next to your code, to deal with object structures that don’t align with your business logic. Handling user input is a good example here. Usually, we use event handlers to deal with all these use cases. And usually these events come with a payload. That’s a specific object structure. We can use an interface to describe the shape of this payload, so that we know what is expected.

In a similar way, you can use interfaces to define the expected structure of a function argument:

interface FormValues {

username: string

password: string

}

const formData: FormValues = {

username: document.getElementById('usernameField').value,

password: document.getElementById('passwordField').value,

}

postToServer(formData)Here we have created an interface that contains a username and a password.

Naming Conventions

Interfaces in TypeScript can be used similar to any other type annotation. To avoid name conflicts, the community is used to add a prefix to all the interfaces.

There is no standard for the naming conventions by the language itself. So, TypeScript will not limit you from choosing any name for your interfaces. It is highly recommended, though, to decide on a naming convention and then use it in your project.

I have seen projects that use the letter I, for example ITrack. I have also seen projects with the words Is , With, or Has, for example, we can have IsTrack, WithId, or HasFileExtentions accordingly. I have seen projects that use a suffix -able, like Comparable or Searchable, to add some unique characteristics to their classes or objects in general.

I have seen projects that don’t use any specific naming convention. For example, if your codebase uses functional programming principles, you probably don’t use the class keyword that often. That leaves you with a flexible namespace, because now you don’t have to separate classes from interfaces.

I have also seen projects that use a combination of the naming conventions above.

In a perfect world, you agree with your team to use a specific name convention, and you follow it with all your heart.

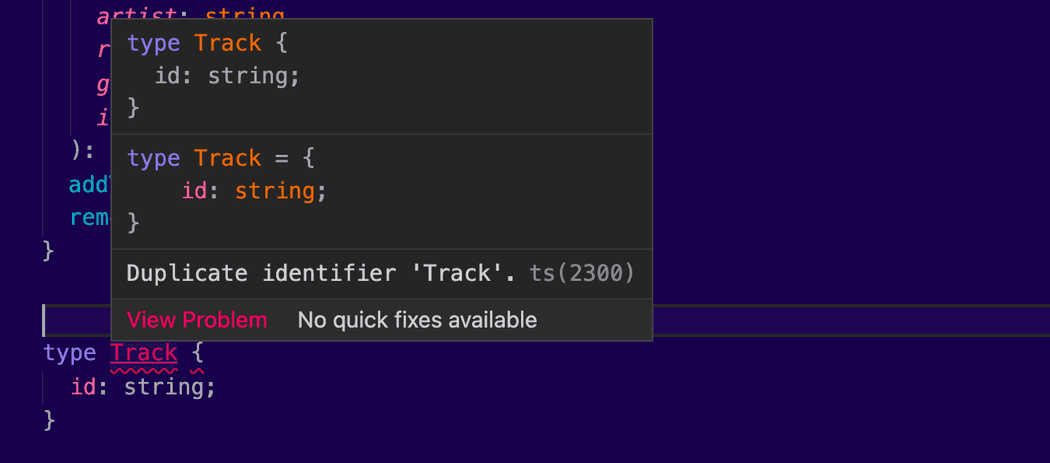

Declaration Merging

The TypeScript implementation of interfaces differs from other programming languages. Declaration merging allows you to declare interfaces with the same name multiple times.

Here’s an illustration of this feature:

interface ITrack {

id: string | undefined

}

interface ITrack {

title: string

artist: string

}By declaring the same interface with different members, we are basically creating a bigger one:

interface ITrack {

id: string | undefined

title: string

artist: string

}TypeScript will merge the previous declarations into one single ITrack interface. Of course, it will complain in case you try to define the same member, with a different type.

This concept of interfaces sets them apart from type aliases, which must have unique names across your project:

In general, I would prefer interfaces over types, when it’s possible. Use type aliases when your objects could be undefined, or if they can act as a different type, like for example a string.

Cover Credit: Sebastian Svenson