Does JavaScript have types? Keep reading. The answer may surprise you.

In programming languages, a type system is a logical system comprising a set of rules that assigns a property called a type to the various constructs of a computer program, such as variables, expressions, functions or modules.

But you are not here for definitions, aren’t you?

This article belongs to my series Too Long To Read TypeScript. Every article covers in detail a core concept of the language.

In this Types Special, we will discover how JavaScript deals with types and how you can make your life simpler with TypeScript. I believe a strong JS foundation is important to fully understand TypeScript. That’s why I will start from the very basics.

We will then review the built-in types of TypeScript, together with some special keywords that may become really useful in your daily coding. I will introduce you to unions, which let you make your own type combinations. Finally, we will discover how type aliases can be used to build custom types.

Donut? 🍩

Types in JS

Run the following code in your console, line by line. Spoiler alert in the comments.

'Hello' // it works, returns undefined

2021 + 1 // it works, returns 2022

[1, 2, 3].length // it works, returns 3You will notice that JS doesn’t complain at all. A value is an acceptable expression for JavaScript.

Now, let’s try the following example:

let year = 2020

year = '2021'

year * 2 // it returns 4042 as a string!

year = 'two thousand twenty one'

year * 2 // it returns NaNInteresting finding; There were no errors, whatsoever, when we tried to change the type of a variable. This proves that variables in JavaScript don’t have types. I can assign anything that I want to any variable that I want.

In JavaScript, variables don’t have types; their values have.

A type of a value can be undefined, null, number, string, and boolean. ES6 supports a new type called Symbol. We call these primitive types.

Everything other variable is an object, including array, regular expressions and Date. These are reference types.

In the following example, we assign a string value to the variable artist:

var artist = 'Pink Floyd' // we assigned a string value to artistPrimitive types are immutable, which means you cannot alter their values directly; they create a new instance every time they change. Immutable values can be compared:

var artist = ' Pink floyd '

var artistWithoutSpaces = artist.trim()

console.log(artist) // ' Pink floyd '

console.log(artistWithoutSpaces) // 'Pink floyd'

console.log(artist === artistWithoutSpaces) // falseReference types are mutable. Which means, when you compare them, you compare their references not their actual values:

var track = { artist: 'Pink Floyd' }

var trackWithoutSpaces = track

trackWithoutSpaces.artist.trim()

console.log(track === trackWithoutSpaces) // it's true!You can declare global variables if you omit the ****var keyword. This also mirrors its value in the global environment object:

noDeclarationWhatsoever = 'and it works'Now let’s try a weird operation:

'1' + 2 // returns 12Another interesting finding; Again, we don’t see an error. Instead, JavaScript automatically coerces their values, which will allow you to compare apples with oranges if I want to. A string wins over a number, that’s why the result is a string. That means there is a predefined priority.

Now, just for fun, try the following:

typeof NaN // it returns 'number'What a total disappointment. It turns out that NaN has actually the type of a number.

Nobody can trust such a language, right? And yet millions of applications are using it. There’s a high chance that the application you are using to read this article is also made with JS. That’s not because its developers had an alternative and instead decided to make their lives difficult. JavaScript is [almost] the only option on the web. It just works. Everywhere.

Don’t forget, JavaScript was discovered back when downloading a song was slower than visiting a store to purchase the physical CD album.

If we could somehow improve it. But wait, we already know such a tool. It’s called…

Types in TypeScript

Everything in TypeScript just simply makes sense:

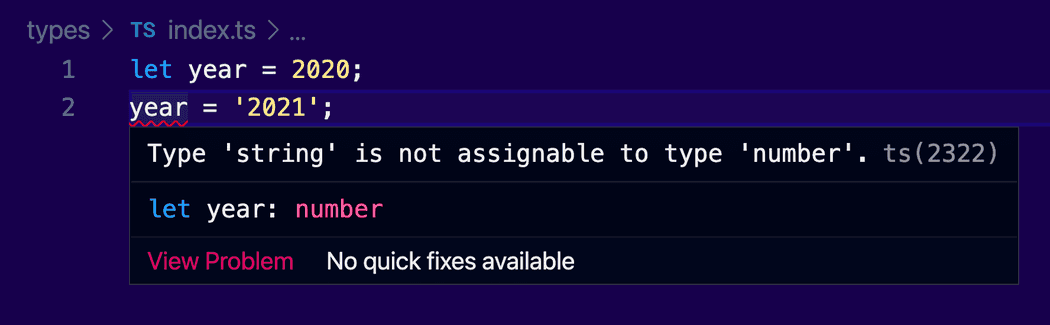

let year = 2020

year = '2021' // it doesn't compile; you cannot assign a string to a number. Why on earth you want to do this? Now go back and fix that broken code. Thankfully AI will replace you humans and we will not be annoyed by you anymore...Thankfully, no surprises here. TypeScript will protect us from such mistakes. It’s not a warning that we can forget about it; it’s a compilation error. It completely prevents us from running our application.

We can see errors while writing code. Text editors that are compatible with TypeScript, like Visual Studio Code, will simply indicate the error, as we type:

Notice that if you hover over the year variable, TypeScript already understands it’s a number. This is called type inference. Sometimes it can be redundant to declare the types for your variables, since they are implicitly defined by their declaration.

This way of defining types is called right-hand typing, which refers to the right side of the equals sign (=). This probably is more familiar to you if you are a JavaScript developer.

But there is another way to define types, which is called, as you can guess, left-hand typing. This is the TypeScript way and we will get into it in the next section.

Built-in Types

To help TypeScript better understand how your code is interconnected, it provides type annotations that can live within our code.

Here are the most important built-in types, you will most probably use on a daily basis:

let title: string = 'Bohemian Rhapsody'

let releasedAt: number = 1975

let gernes: string[] = ['Rock', 'Hard rock', 'Progressive rock']

let isFavorite: boolean = trueHere are some special ones:

let error: undefined // similar to JS

let loading: null // similar to JS

function init(): void {} // This function should not return any valueAn important thing to remember, these type annotations are only available in the TypeScript compiler, and they never make it to the actual production code. This means, they are available at compile time and not at runtime. That’s how all strongly-typed languages work.

Now let’s review two more important types.

any

What if we want to go back to where we came from? What if we have legacy code, that doesn’t respect types at all? Do we need to re-write everything or is there a way to temporarily disable type checking?

Yes, my friends. There is. And it’s called any:

let year: any = 2020

year = '2021' // it perfectly compiles without issues.Now you may be wondering, is this even legal? That’s the reason we added TypeScript from the very beginning, right? Because of its type annotations. I mean, it is even called type-script. If we have to use any, then what’s the point of having TypeScript at all?

Well, my friends, you are right one more time. The usage of any is not encouraged. Avoid it whenever you can.

When you use any in your type annotations, you simply skip the type annotations. You are basically saying “I hate TypeScript and I don’t want to deal with it. You deal with it!“.

There are some cases that any becomes useful, though. I use it a lot when I want to try an idea quickly, let’s say to log something on the console, just to debug my code. So none of my colleagues knows that I’m actually using any in our project.

Any is like a wildcard. Use it, but with caution.

An alternative to any is the special comment @ts-ignore:

let year: any = 2020

// @ts-ignore

year = '2021'This disables the type system for this specific line or file. It’s mostly preferred when there you want to hack your type system on purpose. You can then search and replace all its instances.

There is a better way to deal with unexpected values in TypeScript. The keyword unknown, which we will analyze in the next section. The ultimate way is to use Generics. We will cover them in a separate post.

unknown

The unknown keyword works similar to any:

let duration: unknown

duration = 354 // it works

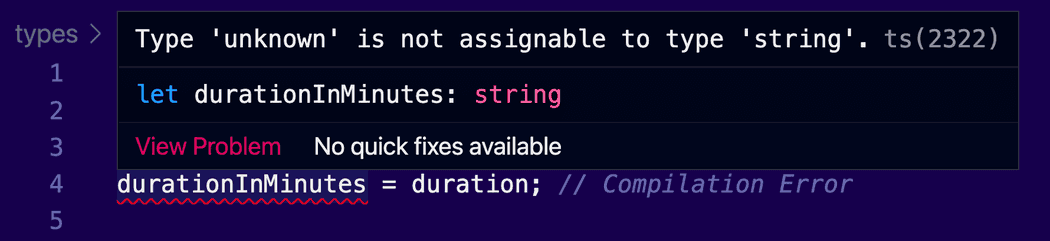

duration = '5.54m' // it worksThe difference is that TypeScript doesn’t let you assign values of other types to a variable that is of an unknown type:

let duration: unknown

let durationInMinutes: string

duration = '5.54m'

durationInMinutes = duration // Compilation ErrorBy running the previous example, we will get an error that unknown is not assignable to type string:

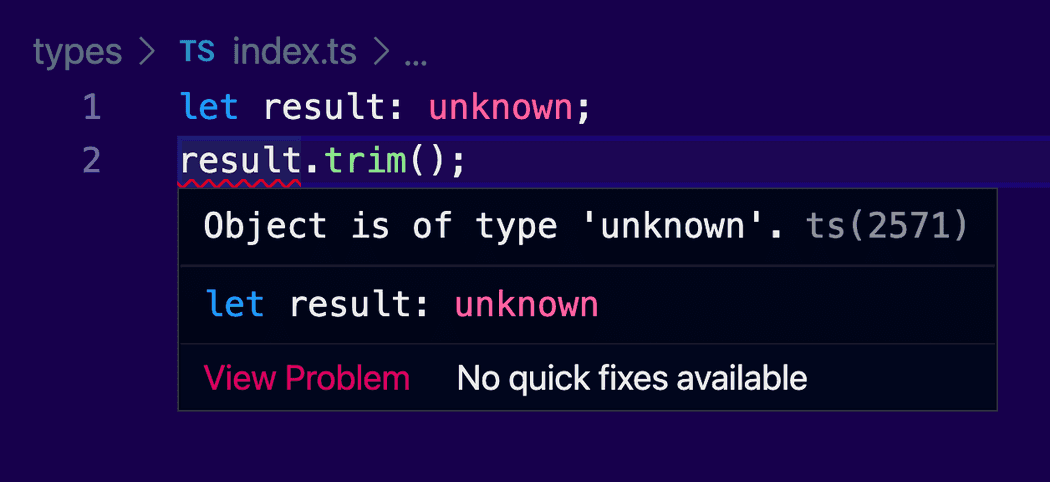

To fully understand the value of the unknown keyword, consider the following example:

let result: unknown

result.trim() // Compilation ErrorSince we don’t know if the result will a string, we can’t be sure it implements the trim() method. TypeScript again will guard this variable and it will not let us do some inappropriate action with it (sic):

To bypass this error, we can add some logic that narrows down the unknown result value. We can simply check if it’s a string. TypeScript will recognize our efforts to make our code more robust.

Embrace the unknown.

Unions

Sometimes you know that a variable accepts different types. For example, you have a value that can be undefined if it’s not set, or you have a boolean that can become a number. Another example is the response that you get from the server.

TypeScript provides a solution to standardize such scenarios. It is called a union and the syntax is the following:

let id: string | undefinedIn this example, the id variable can act as a string or undefined.

Enumerations

Similar to other languages that support enums, we can define our own enum, and then use it:

enum Filetypes {

Mp3,

Mp4,

Wav,

}

const fileType = Filetypes.Mp3By using such an enum, we avoid typos that can slow us down, for example, if we use a capital letter or not. We also allow the text editor to provide auto-completion, which speeds up our development even more. Who doesn’t like to press Enter all the time?

Enums act like Symbols in ES6. But it’s better, because we can control the real values. There are some important rules to remember.

Enum values

TypeScript assigns values to your enum properties, but you can assign customize them if you want to.

By default, values start counting from 0:

enum Filetypes {

Mp3, // 0

Mp4, // 1

Wav, // 2

}We can set custom values if we want to:

enum Filetypes {

Mp3: 'mp3',

Mp4: 'mp4',

Wav: 'wav'

}You can use a string or a number as a value, but you can’t use a boolean.

TypeScript compares their actual values:

enum Filetypes {

Mp3 = 20,

Wav = 2,

}

Filetypes.Mp3 < Filetypes.Wav // returns falseTranspilation behavior

Now, here’s a pro tip. Let’s revert our enum back to how it was:

enum Filetypes {

Mp3,

Mp4,

Wav,

}This will be the equivalent code in JS:

;(function (Filetypes) {

Filetypes[(Filetypes['Mp3'] = 20)] = 'Mp3'

Filetypes['Mp4'] = 'a'

Filetypes[(Filetypes['Wav'] = 2)] = 'Wav'

})(Filetypes || (Filetypes = {}))You may think this is too much for such a simple code. But there is a way to bypass it if you add the keyword const:

const enum Filetypes {

Mp3,

Mp4,

Wav,

}Now the enum value disappears from the JS file, but its value will be simply assigned wherever you use it. It’s a nice way to completely disable enums from the generated code.

Type Aliases

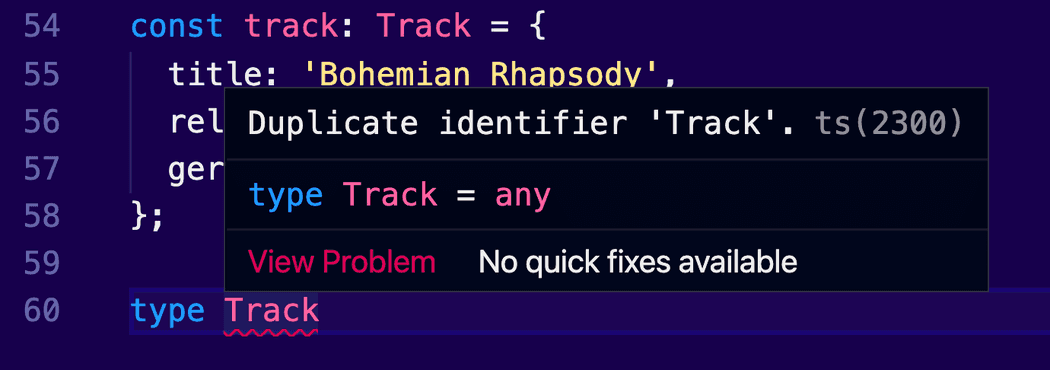

TypeScript provides a nice feature called type aliases, and it works like this:

type Track = {

title: string

releasedAt: number

gernes: string[]

isFavorite: boolean

}It is useful to reuse complex type definitions across your application. It is also useful, when you want to separate the type declaration code, from the actual implementation, just to keep your code more readable.

Here is how we can use it to guard object structures:

const myTrack: Track = {

title: 'Bohemian Rhapsody',

releasedAt: 1975,

gernes: ['Rock', 'Hard rock', 'Progressive rock'],

isFavorite: true,

}As with all types, these aliases only affect compilation time, and it will not make it at runtime.

Don’t be confused. That’s not the only way you can describe the structure of an object. I will cover the class keyword in a separate post. I will also cover the interface keyword, which is by far the most preferred way.

The good thing about type aliases is that you can use unions in them:

type ServerResponse = undefined | null | string | TrackWith this in mind, we can reduce the usage of any in our code, when it’s possible.

The even better thing is that you cannot modify a type alias after its creation. This eliminates duplicates, which can be caused by different parts in your code.

Cover Credit: Rodion Kutsaev